In Art, China’s History With the Horse Is a Glorious Story

This is the second article in a three-part series on the history of horses in China, which we’re running to usher in the Year of the Horse. Read Part 1.

The Year of the Horse is upon us. Throughout Chinese history, the horse has been a dependable means of transport on bustling streets, a reliable courier between distant relay stations, and vital military equipment on the battlefield.

The horse has also galloped through millennia of Chinese literature and art. Artisans molded it in clay, painters captured it in ink, and poets celebrated it in verse. From these countless equine-inspired works, we witness not only how the horse has accompanied human civilization but also how its spirited nature, bravery, and loyalty have made it an enduring embodiment of virtue and noble character.

Gene and totem: The making of a bronze symbol

In 1969, a sculpture later named Bronze Galloping Horse was unearthed from a Han dynasty (206 BC–AD 220) tomb in northwestern China’s Gansu province. With its head held high, tail aloft, three hooves in the air and one poised lightly on the back of a flying swallow, the statue transforms a sensation of sheer speed into one of weightless buoyancy.

Today, it ranks among China’s most iconic cultural relics, and its image has been adopted as the national symbol for Chinese tourism.

No one can remain unmoved by the breathtaking sense of balance it embodies: the entire sculpture is supported by nothing more than a hoof surface — less than a few square centimeters — resting on the bird’s back. With genius-like artistic intuition, the caster placed the horse’s center of gravity precisely on the vertical line above that single point of support, so that heavy bronze acquires, to the eye, an absolute stability, while still keeping an unstoppable forward drive and an almost impossible lightness. What stands before us is a miracle that fuses motion and stillness, sprint and gravity, into one.

More importantly, the horse’s arched neck, streamlined torso, and slender yet powerful limbs are not merely products of artistic imagination. Scholars suggest that, judging from its robust and elegant physique, it is very likely a depiction of the “Dayuan horses.” These horses — whose name comes from the Chinese name for a civilization in what is now Central Asia’s Ferghana Valley — were animals the Han dynasty tirelessly sought.

This bronze steed was unearthed in the Hexi Corridor, the slim part of present-day Gansu province that was a vital trade route to Central Asia, bringing into focus a history of searching for and breeding superior horses: In the early years of the Han dynasty, although the imperial court vigorously developed horse husbandry, the quality of the stock still urgently needed improvement.

Consequently, acquiring superior breeds from Central Asia to improve local strains became a top priority for Han rulers. Emperor Wu of Han, while expanding the state herds, appointed Li Guangli as a general to launch a war against Dayuan aimed at seizing fine horses. According to the Book of Han, Li launched two expeditions and returned with “dozens of their finest horses, and more than three thousand stallions and mares of medium quality and below.”

Since then, the bloodline of Central Asia’s “heavenly horses” flowed into the herds of the Han heartlands, the Central Plains. Generations of herders undertook what might be called the earliest form of “genetic engineering”: by blending the endurance of Mongolian stock with the speed and explosive power of Central Asian breeds, they ultimately forged the “Hexi Heavenly Horse,” renowned for both its majestic form and combat prowess. The Bronze Galloping Horse stands as the ultimate artistic tribute to this centuries-long, persistent epic of equine cultivation.

Body as battleground: The monumental six steeds

The continuous introduction of horse breeds from Central Asia significantly enhanced the quality of Central Plains stock, a trend that persisted into the Tang dynasty (618–907).

In the year 649, Emperor Taizong passed away. Guarding the approach to his mausoleum — the Zhaoling Mausoleum in Liquan County, Shaanxi province, northwestern China — were six stone reliefs depicting horses: the “Six Steeds of Zhaoling.” These masterpieces are not only superb examples of the introduced Turkic horse breeds prized by the Tang but also key to understanding the inner world of a great emperor and the profound significance of the horse, which transcended its role as a mere strategic and economic asset.

These six steeds were divine colts that performed meritorious deeds in the campaigns Emperor Taizong fought to establish the Tang dynasty. They possessed their own names: Quanmaogua (“Curly-Haired Yellow”), Shifachi (“Red”), Baitiwu (“White-Hoofed Black”), Telebiao (“Tele Yellow”), Qingzhui (“Green/Black Piebald”), and Saluzi (“Whirlwind Purple”).

Many scholars have researched how their names point to their Turkic lineage, and beyond indicating their origin, the names commemorate them as recognized individuals, credited for their specific achievements. Each one corresponds to a pivotal battle and a moment of mortal peril in the life of the late emperor. Thus, they were endowed with a historical identity nearly equal to that of their human sovereign. They were not silent accessories, but co-authors of the dynasty’s founding narrative and living testaments to its merit.

Viewing them through the lens of this “horse-human” relationship, we find that the Six Steeds of Zhaoling are not the representation of triumph one might expect. Arrow wounds, injuries, charging, healing — these highly narrative and cruel details declare that their very bodies were the battlefield. The perils of war and the hardships of empire-building need not be described in words; they are inscribed into the stone flesh of the Six Steeds.

The reliefs also depict a rare emotional symbiosis in imperial art. In the Saluzi relief, the Tang general Qiu Xinggong is shown bending to extract an arrow from the horse’s chest. Within a shared frame of vulnerability, man and horse tend to and depend on one another. No figure assumes the overbearing posture of a conqueror here; instead, the general places himself in a position of shared fate with his steed. The Emperor’s image is absent — or rather, the horse’s bravery, endurance, and loyalty become the very embodiment of the Emperor’s heroic spirit and his ideal for the bond between ruler and subject.

In this way, the Six Steeds of Zhaoling perfectly translated the political into visual form. Erected in the sacred space of the imperial tomb, they became permanent monuments to the Emperor’s legacy, materializing intangible qualities like speed, power, and sacrifice into enduring, venerable images. Here, the horse is no longer just a resource of war, but a symbol of the monarch’s prestige and courage — a monument to the empire’s founding legitimacy itself.

From sport to spectacle: The equine pageantry

If horses on the battlefield carried the burdens of life, death, and merit, then in times of peace and prosperity, they became stars upon the stages of sport and spectacle. Polo and Dancing Horses are two quintessential examples.

Scholars generally agree polo was not native to the Central Plains but was introduced and localized during prolonged cultural exchanges with Central and West Asia. Nobility from the Parthian (247 BC–AD 224) and Sasanian (224–651) Empires long held the game in high regard. With the opening of the Silk Road, polo spread rapidly during the Sui (581–618) and Tang dynasties. Several Tang emperors, notably 9th-century Emperor Xuanzong in his youth, were renowned for their skills. For them, polo was more than sport or martial training; it was a political performance centered on equestrian prowess and courage, an externalization of imperial confidence.

This fashion left vivid evidence in the visual record. The Polo Mural from the Tomb of Prince Zhanghuai in Shaanxi shows over 20 riders galloping back and forth: some turning to strike, others vying for position, with a possible referee watching intently. The complex composition captures a tension akin to a cinematic ensemble.

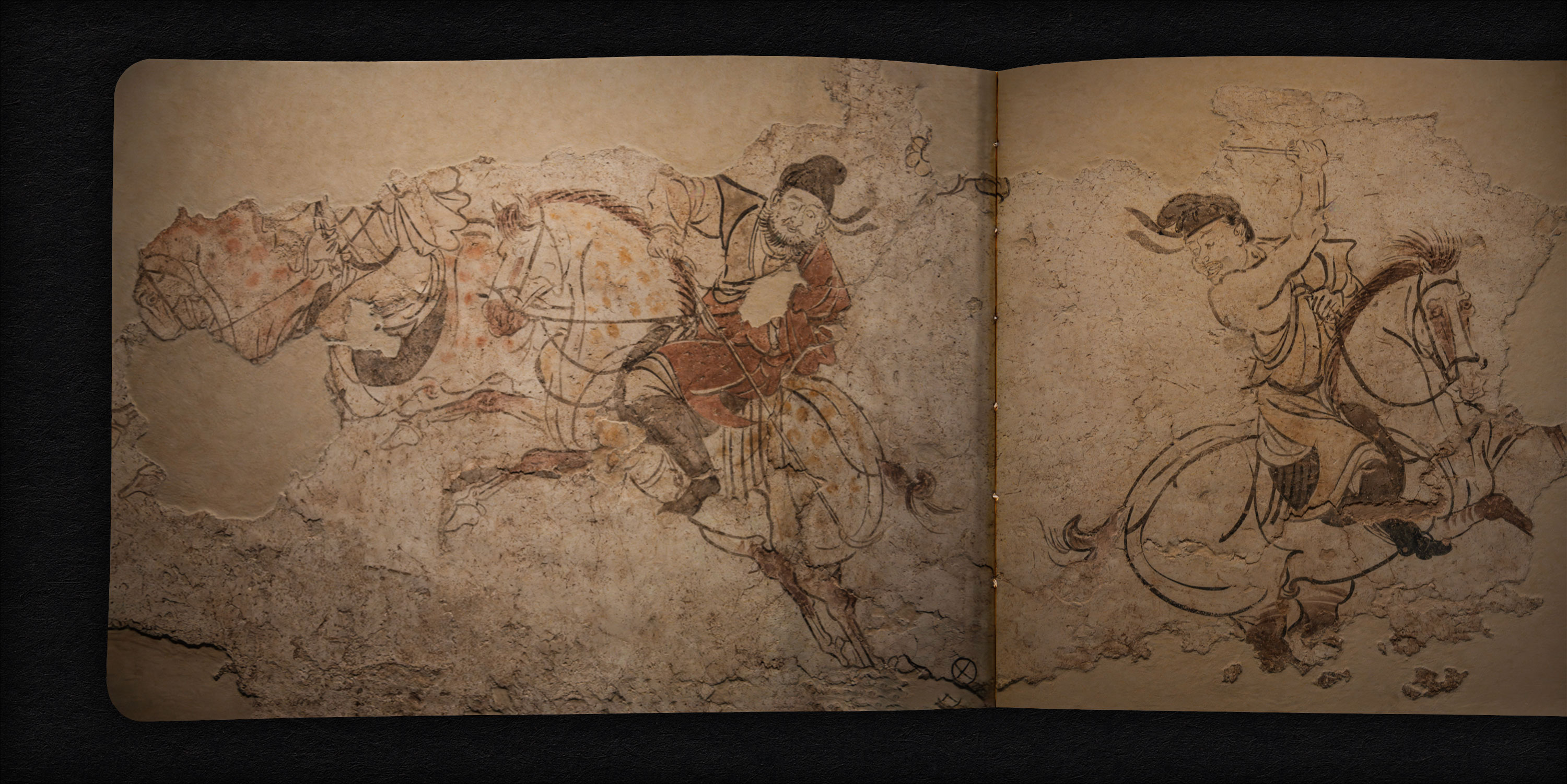

By comparison, figures in the Polo Mural from the Tomb of Li Yong, also in Shaanxi, are portrayed in a tighter “close-up”: their gazes locked on the ball, headscarf tails streaming in the wind. The swift, precise lines depicting the horses reveal Tang artists’ deep familiarity with both equine form and the sport itself.

If polo emphasized confrontation and victory, then Dancing Horses elevated equine training into a refined aesthetic realm. Dancing horse performances reached their climax during the reign of 8th-century Emperor Xuanzong, considered the era when the Tang dynasty peaked. According to historical records, dozens or even hundreds of horses would dance simultaneously in group performances. For example, the “Record of the Wenguan Hall in the Jinglong Era” notes palace performances where horses “held cups in their mouths, lying down and rising again.”

A “Gilded Silver Flask with Dancing Horse and Cup Design,” unearthed from the Hejiacun Tang Dynasty Hoard in Shaanxi, provides a visual. The body of the vessel uses a molding process to depict two dancing horses kneeling and clenching cups: the horse’s hind legs squat, ribbons flutter at its neck, a wine cup is held in its mouth, and its tail is raised high, as if dancing to music, brimming with extraordinary artistic charm. This image provides rare and intuitive physical evidence for the Tang dynasty dancing horses, which are frequently mentioned in literature but have long been lost.

The poet Zhang Yue, in his “Lyrics for the Dancing Horses at the Emperor’s Birthday Celebration,” wrote, “At the final strain of the banquet’s song, the dancing horse grips the winecup/lowering head and tail, drunk as if sunk in mud,” indicating that the pattern on the silver flask is a realistic scene, depicting the closing movement of the dancing horse performance at the end of a banquet.

This exquisite domestication and ultimate entertainment of dancing horses declined rapidly with the collapse of the dynastic order after the An Lushan Rebellion (755–763). The horses that once danced in palaces were scattered, and this fragile mode of spectacle faded with the dynasty’s prosperity, never to fully return.

It is evident that horses not only drive history as tools of war but also witness history; their fate has been closely linked to the rise and fall of the times. In both competitive gallop and choreographed dance, humanity has long marveled at the horse’s power and grace, simultaneously inscribing its own ideals of authority and beauty upon the equine form.

(Header image: Details of the Polo Mural from the Tomb of Li Yong. Visuals from VCG, reedited by Sixth Tone)